I was lucky both times when I went inpatient for psychiatric care. I had no illusions about what I was doing. As scary as the prospect of going inpatient was, I knew what to expect packing-wise.

So, first off, how do you even know that you even need to go? Well, it’s a bit of a crap shoot. While I thought knew both times, the second time, I was less sure.

The first time was crystal clear. My level of functioning had been steadily declining. Most days I was too anxious to leave the apartment, so I worked from home. I mostly spent the days having panic attacks, snuggling with my kitties, and watching “The Next Great Baker” to calm down. Rather than go to the ER for a migraine on my own, my mother came to get me and took me to a hospital further away from my home and closer to hers. She came to my apartment the next day to take me up to see my grandmother who was in the hospital an hour north, fighting pneumonia for the umpteenth time. I had a panic attack all the way there, and all the way back.

Monday, I knew I couldn’t make it out of my apartment to go to my therapy appointment. I was too scared. Mom once again came to my apartment. Normally, I might call my mom once a week, and see her maybe once a month. It was rare for her to come to my apartment multiple times a week. So, on that Monday, she gave me an ultimatum: go inpatient or come live with her for an undetermined amount of time.

Moving back to my parents’ house was never an option for me. To cut a long and pretty dark story short, that house was a symbol of a lot of abuse I had suffered as a teenager. Going back, particularly when I was so emotionally fragile, was simply not an option.

Also, it was 45 minutes away from where most of my life took place. That might not seem like much, but it would be highly isolating for me.

My mom drove me to my therapy appointment. She met my wonderful therapist. Then, she waited in the waiting room. I told my therapist what was happening. I think that this is a very important step. My therapist determined that while I wasn’t actively suicidal, I was close to “shut down”.

“Basically, that meant that while I didn’t have an active plan to end my life, if a train was coming at me, I wouldn’t have the energy or desire to move off the tracks.”

My therapist called the local behavioral health unit. They have an access line specifically for emergencies like mine. They confirmed that they did take my insurance, and that there was a bed available on the unit for me, and we arranged a time for me to come in.

Step one was over. Step one was admitting that yes, I needed help, as cliché as it sounds. Step one part b was getting in contact with the hospital, and establishing when I would go in. For anyone in crisis who doesn’t currently have a therapist, there are a couple of ways you can get to this point. For my second inpatient hospitalization, I called my primary care physician, because I couldn’t reach my psychiatrist (I was having a horrible reaction to Abilify) and neither could I reach my therapist. A quick Google search found me the behavioral unit’s phone number.

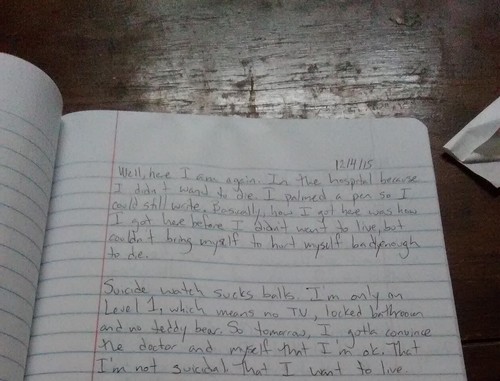

It’s daunting, knowing that you’ll be going for inpatient treatment without knowing how long you’ll be in the hospital. I highly suggest asking what items aren’t allowed in the unit. I knew most of these already, since my stepsister had been placed inpatient when I was much younger. Expect that anything with a string will either have to have that string removed, or be left out of your suitcase. Different units have different ideas about what counts as contraband. The usual things are cell phones, any electronic devices, no weapons, no drugs, no items that could be used in a suicide attempt. My unit had a couple of odd things on their contraband list. Teddy bears were contraband. I was allowed my teddy bear after asking the doctor if I could have it, so some things are flexible. The important part here is to pack well. The unit might be too cold or too hot, so pack in layers (the unit I was on was freezing all the time). Despite the group therapy classes and meetings with doctors, it is very likely you’ll have a lot of free time. I packed a lot of books just for this purpose. Some rooms have TV’s in them, but you certainly aren’t guaranteed to have a TV in your room. I also packed a journal.

This journal saved my bacon in many ways. First, I was able to self-express in a way that was already comfortable. Second, I wrote down every darned thing the doctors told me. This would be useful later when their orders didn’t get through the hospital hierarchy, so when the nurses were about to give me the wrong dosage of a medication, or continued to have me on suicide watch even though the doctor told me I was clear, I could point to my journal and say, “I wrote it down.”

The hardest thing to handle out of all of this, for me, was the isolation. In my unit, cellphones weren’t allowed. Visiting hours were only a couple of hours each day and phone calls could only be to local numbers, and only ten minutes max. Throughout my depression and anxiety, I relied on reaching out to my friends and family via text, email, and social media. To have that suddenly cut off was both a blessing and a curse.

On the drive to the unit, I was able to text all of my friends to let them know that I would be incommunicado for a while. Their responses ranged from the cold “I wouldn’t do what you’re doing, but whatever” to “I’m sorry that you’re in pain, I love you, and I’ll be here when you get out”.

The intake process was terrifying, but also boring. The first time, my parents and my boyfriend stayed with me. The second time, my boyfriend stayed with me. Basically, the nurses ask you tons of questions. The process takes about an hour. Everything from “When was your last period?” to “What brings you here today?”

After about an hour of questions, you have to say goodbye to your loved ones. This was hard. Even though my boyfriend promised to come see me as often as visiting hours would allow, it’s scary to know that you’ll be alone in this strange place.

After that, the nurses have you give a urine sample (both to check for drugs and to make sure you aren’t pregnant) and they check your skin for signs of injury. Basically, you go into a private room with the nurse, and you strip to your skivvies and the nurse writes down any marks on your skin. Mostly, this is to catalog self harm scars and any infections you might have. You dress, get a tour and a basic schedule of daily activity on the unit, and then you’re left to your own devices (until the next scheduled event).

Most of my days went like this: Wake up. Eat breakfast. Have a community meeting where we talked about our goals for that day. Shower and change clothes. Go to the first group therapy session. Have about an hour of free time (I used this to read, watch Food Network, and journal). Go to the second group therapy session. Have lunch. More free time. Go to the third group therapy session. More free time. Dinner. Visiting hours. More free time. Go to the second community meeting where we talk about the goals we completed that day. More free time. Lights out at 11pm.

Spattered in there were blood pressure and vitals checks, medication administration, meetings with the psychiatrist, the social worker, and the hospitalist (by law, you have to see a hospitalist at least once during your stay, just to make sure you don’t have additional health concerns). It’s very tedious, repetitive, and boring.

Yes, boring. Honestly, the hardest thing I had to deal with while I was an inpatient was the mind numbing boredom on the unit. Like I said, I was lucky. About half of the patients who came onto the unit while I was there didn’t know that they would be staying for any longer than a few hours. It’s hard enough to admit that you need help, to go and get that help, and not have anyone prepare you for the fact that you might be in the hospital for a few days, that you’ll need to pack extra pairs of clothes, and other various whatnots.

It was very isolating to not be able to text my friends while I was there. That said, for the most part, the unit was quiet. However, being inpatient did help me develop tools to help cope with my mental illness.

Being inpatient for psychiatric care was not as scary as the media makes it out to be. Sure, there were unsettling moments. My first inpatient stay, there were a lot of volatile personalities. People screamed, fought each other, punched walls, and even punched fiberglass windows. However, for the most part, it didn’t bother me. Yes, listening to yelling and screaming is uncomfortable, and repressing the desire to go towards the screaming and offer assistance is difficult, but one thing made me feel relatively safe while I was there.

“I was nice to people. Since I treated people like people, no one wanted to fight me, which suited me just fine. The yelling, screaming, fighting, punching…none of it was directed towards me. Most of it wasn’t really directed at people. It was people reacting to having a really, really bad day and being extremely outside of their comfort zone and feeling like they had lost control.”

I actually had one of the ladies who frequently got into fights, while she was angry, tell me, “If Ashley comes over to me again, I’ll punch her right in the face. I’ll beat them all up. Not you though, because I like you.”

The exit process is much easier than the intake process. Basically, you fill out a lot of paperwork on how you’ll adjust back to your home life. You make an emergency plan for what happens if bad days happen (and they will). You have final interviews with the social worker, the psychiatrist, and the nurses.

And then, your loved one or friend picks you up (they have to discharge you to someone. I didn’t see anyone leave by themselves). It’s odd at first, adjusting to being back in the world. I missed my phone. I missed my cats, and cuddled with both of them when I got back. The first time I came out of the hospital, I had what is called a “flight to health”. Basically, I was so freaked out by being in the hospital that I frantically did everything that I thought would get me out of that place. That came back to bite me in the rear, because I ended up back in the hospital about a month later. As difficult as it is to stay inpatient, staying until you’re really ready for discharge can help you avoid a second stay.

Maybe this article isn’t one most cohesive things I’ve ever written, but one thing is very clear to me in the aftermath of my experiences. We have been taught to fear the psych ward, primarily by the media and our culture. This is ridiculous.

“Going into a hospital for any type of treatment is scary enough, why would we masochistically terrify ourselves about inpatient psychiatric care when we need it most, at those most emotionally vulnerable times in our lives? Perhaps it’s the fact that psychiatric care has been abused in the past. Perhaps it’s how we demonize mentally ill people currently. Either way, it has got to stop.”

This demonization of mental health care only keeps people from getting help that they might desperately need. It makes getting help more stressful than it needs to be. Not only that, but choosing to get help becomes this stigmatizing issue that pits friend against friend.

While my journey to get mental health help certainly wasn’t comfortable, it wasn’t terrifying. So far, it has been my most difficult hospital stay, mostly because of the social isolation. We need to remove the stigma from choosing to get mental health help, so people are no longer afraid to get whatever help they need to get well, even if that help is an inpatient stay on a psych ward.